Traditional 4th Of July Foods: Where Did They Come From?

The 4th of July is “Independence Day” in the United States. In the U.S., we celebrate this day we’ve chosen as our “National Day” much the same way most celebrations happen all around the world, we eat. A lot!

But with a few yummy exceptions, most of the foods we eat did not originate here in the United States or even in the Americas. So, where did all of the traditional 4th of July foods come from?

As a country of immigrants, what is unique and natural is that our favorite “feast day” foods originated from places worldwide.

This article may contain affiliate links. We may earn a commission if you use these links to buy products or services. Please see our disclosure policy for full details. Thanks.

You Can’t Get More Traditional 4th of July Foods Than Barbecue (BBQ)

A summer tradition and maybe an obsession for many is barbecue. We love to cook our meat outdoors on a grill. Brisket, beef ribs, and baby back pork ribs are the mainstays of barbeque here in the U.S., but chicken is on the grill as well.

But barbecue didn’t start here in the U.S. You have to look far afield for its beginnings. Humankind has been cooking meat outdoors since way back.

In South Africa, Braais have been part of informal gatherings of family and friends for as long as anyone can remember. It’s believed the word Braai comes from braaivleis – Afrikaans for “roasted meat.” Meats prepared for a braai are lamb, steaks, spare ribs, sausages, chicken, and fish. People attending a braai are expected to bring snacks, drinks, and other meat to eat until the main meal has finished cooking. Sound familiar?

The English word barbecue may have its roots in the language of the Caribbean Indian tribe called the Taino. Their word “barbacoa” first appeared in print in a Spanish explorer’s account of the West Indies in 1526, which meant grilling on a raised wooden grate. This time-honored method of cooking meat over a grill or pit, covered in spices and basting sauce, got revved up in the Caribbean!

Today many folks like using gas grills, easier to start and no coals to worry about. And, while convenient, these grills are often frowned upon by barbeque aficionados. Charcoal is accepted, but wood is seen as the best, and even campfires are often used for cooking the meat.

I’m pretty fond of baby back ribs Memphis style. Still, you may enjoy Carolina pulled pork sandwich, Kansas City “burnt ends,” or Texas smoked brisket. Whichever style of barbecue you have as traditional 4th of July foods, give a nod to your ancestors to thank them for bringing this food to your table.

Are you planning your 4th of July picnic/barbeque at the beach? Take along this cute little Weber Smokey Joe!

Hot Dogs And Hamburgers Anyone?

Hot Dogs and Hamburgers are pretty traditional 4th of July foods. In fact, you can usually find one or the other on backyard grills all summer long. You think you know where they came from, after all, isn’t their origin practically in their name?

Hot Dogs, AKA “Frankfurters”

With a name like “frankfurter,” could hot dots have a more straightforward history? While there is some argument about whether the now-famous sausage originated in Frankfurt or Coburg, there is no doubt they got their start in Germany.

Once these tasty sausages got to the U.S., we wrapped them in a “bun” and began covering them with whatever we could find. Relish, onions, mustard, ketchup, cheese, chili, pickles, you name it folks in the U.S. covered their hot dogs with it and chowed down.

While often on the backyard grill, you will always find hot dogs at the ballpark. After all, who can sit through a baseball game, America’s National Pastime, without a juicy hot dog and a beer?

The Short Story of How Hamburgers Became a Traditional 4th of July Food

Hamburgers have a more storied history. It’s thought that minced beef was first eaten by Mongol horsemen (remember Genghis Khan). In the 13th century, it made its way to Russia, known as Steak Tartar (tartar being the Russian name for Mongols).

After some refinements in Russia, this raw delicacy made its way to Hamburg along trade routes on the Baltic Sea. Hamburg was considered to have some of the finest cattle and hence beef. By the 17th century, minced meat had become a popular dish of the Germans who fried it or stuffed it in sausages.

In the 18th century, the “Hamburg steak” made its way across the Atlantic to the U.S. via the Hamburg-America line, bringing thousands of immigrants to the New World. Soon Hamburg-style beef patties were served at eating stands all across New York.

We know how Hamburg steak made its way to the U.S. But, when was it first made into the sandwich we know and love, and who came up with this creation? Well…

The Library of Congress records Louis’ Lunch in New Haven, Connecticut, serving minced beef patties between slices of bread in 1895. And Louis is still serving hamburgers the same way today.

But two other folks claim they beat Louis to the punch.

First, we have “Hamburger Charlie” Nagreen. The story has it that in 1885 Charlie was having little success at selling meatballs at a county fair in Seymour, Wisconsin. So he decided to put the patty between two pieces of bread to make it easier to eat on the move.

Then there were the Menches Brothers, who claimed to have invented the dish at an 1885 county fair in Hamburg, New York. Rumour has it that the brothers ran out of pork for their sausage patty sandwiches. When that happened, the Menches switched to minced beef flavored with coffee and brown sugar instead, and a new sandwich was born.

Fried Chicken – With Or Without The Waffles!

You can’t imagine food from the Southern U.S. without Fried Chicken. But chickens were being fried way before the U.S. was the U.S.

Apicius, also known as De re culinaria or De re coquinaria, is one of the earliest known cookbooks in recorded history written around 1 C.E. (or A.D.) contains a recipe for fried chicken.

The Scottish were probably the first Europeans to deep fry their chicken in fat. They likely brought this method of cooking chicken with them when they immigrated to the New World.

Meanwhile, in West Africa, there was also a tradition of seasoning and frying chicken by battering and cooking the chicken in palm oil.

Scottish frying techniques and West African seasoning techniques were combined by enslaved Africans and African Americans in the American South. Thus, “Southern Fried Chicken” was born.

It’s important to remember that initially, fried chicken was a spring and early summer dish. The high heat and fast cooking time of frying meat were too quick to tenderize tough old birds. You need to use the young tender birds for this delicacy.

Potato Salad Quickly Found Its Way To The List of Traditional 4th of July Foods

Potato salad originated in Germany. You don’t have to believe me; our friends at Wikipedia have it there in black and white. From Germany, it spread through Europe, the European colonies, and later Asia.

When Japan finally opened its borders in 1852, it found a renewed curiosity for all things Western, including foods. The Japanese variation of potato salad known as “potetosarada” is most likely derived from the Russian Olivier salad.

This version of potato salad traditionally consists of mashed boiled potatoes, cucumber, onion, carrot, boiled eggs, and ham. These ingredients are mixed with “Kewpie” mayonnaise (they only use egg yolks), rice vinegar, and karashi mustard. This would explain why when my good friend makes potato salad; many of these ingredients are in there.

American potato salad most likely originated from recipes brought to the U.S. by German and European immigrants during the nineteenth century. From then it quickly found its way onto the list of traditional 4th of July foods. Most families have their favorite recipe. If you don’t have a great potato salad recipe, feel free to use mine!

Plan to have potato salad on your picnic table this summer? This salad bowl with a lower bowl just for ice will keep your salad chilled for hours.

Potato Salad and Baked Beans also go great with Beer Can Chicken. This way of cooking chicken gets you out of the kitchen!

Baked Beans – From Boston to Fabada

People around the world enjoy baked beans. Just about every culture has its version of a stewed or baked bean dish. Humans have been cooking up beans in a pot for centuries. Some great examples are Spanish “Fabada,” Egyptian “Ful Mudammas,” Boston Brown Beans,” and Mexican “Frijoles de la Olla.”

With beans, however, we first see what may indeed be an “American Dish.” One version of baked beans harkens back to eastern Native American tribes, particularly the Iroquois, Narragansett, and Penobscot. Their method involved taking soaked native or “navy” beans, mixing them with bear fat (yum) and maple syrup. Next, they would slowly cook the beans in earthen, or deer-skin pots hung over a fire.

Once the dish was adopted and adapted by the colonists in New England in the 17th century, baked beans rapidly spread to other regions and into Canada in cookbooks published in the 19th century.

Many of the early immigrants to what is now the U.S. were Puritans. Their religion did not allow for working on Sunday, the Sabbath. No work meant no cooking. Legend has it that folks would prepare the beans on Saturday and keep them in the warm wood oven until Sunday. Thereby having a hot meal at the end of the day.

If beans are one of the traditional 4th of July foods on your table, that makes total sense. No matter how you cook them, beans have always been a tasty and inexpensive way to feed a crowd.

Corn On The Cob – The Original Street Food

Corn on the cob is an American summer icon. Corn is a hallmark of the heartland’s landscape. You’d be hard-pressed to take a road trip through the midwest and not see fields and fields of corn growing.

But did you know that corn is one of the only crops indigenous to the New World? Corn, or maize as it’s called in many native languages, was first cultivated in Mexico more than 7,000 years ago. From there, it spread throughout North and South America.

This hearty grain was first introduced into the southwestern U.S. from Mexico through highland corridors along the Sierra Madre Mountains. It appeared in the New Mexico or Arizona area some 4,000 years ago.

When Columbus landed in the Caribbean (although mistakenly thinking he was in the West Indies), he and his crew were introduced to corn. Of course, Columbus brought the grain back to Europe with him, and it quickly grew in favor. Now we have fantastic Italian Polenta on our tables as well.

Corn on the cob is a U.S. classic you will find on picnic tables, on the grill, and in a good New England Boil. But the rest of the world is chowing down on these cobs too. Known as Elote in Mexico, you can find corn cobs boiled or roasted and served on a stick to make it easy to hold.

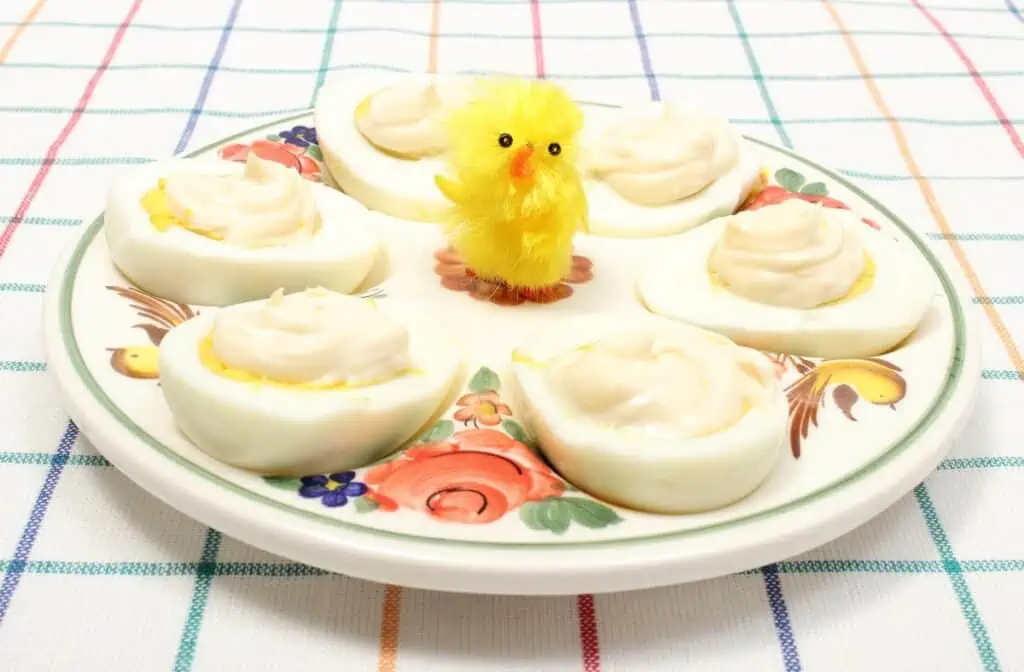

Deviled Eggs

Deviled eggs are also called stuffed eggs, Russian eggs, or dressed eggs, depending on where you’re from. These tidbits are simply hard-boiled eggs, shelled, cut in half, and filled with a paste made from the egg yolks.

You can find recipes for boiled, seasoned eggs as far back as ancient Rome, where they were traditionally served with spicy sauces as a first course.

The idea of mashing the yolks and stuffing them back into the whites gained traction throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. The description of “Deviled” first shows up around 1786, referencing the spicy seasonings such as mustard and pepper with which these eggs were prepared. My recipe for deviled eggs is not as spicy as some, but they always disappear fast from the table.

The U.S. took a bit longer to catch on to the stuffed egg craze. And you might be surprised to learn that mayonnaise wasn’t always the main ingredient. But Deviled Eggs were a cookbook staple by the 19th century.

Fannie Farmer had Deviled Eggs in her cookbooks. She was the first to suggest using mayonnaise — now an integral part of most deviled egg recipes.

Your deviled eggs are a work of art! Make sure to frame them properly.

Hearty Southern-Style Buttermilk Biscuits

If you are looking for a biscuit in the U.S., you are most likely looking for a savory, fluffy southern-style biscuit. (Want an easy recipe for homemade buttermilk biscuits?) In Europe, the term biscuit is now more commonly associated with the sweet versions of what we in the United States call cookies.

However, the biscuits we eat today in the U.S. are relatively modern culinary creations. Historically, biscuits weren’t at the center of hearty breakfasts or Sunday suppers; they were hard, thin, durable, dry, and meant for survival.

The earliest foods we might call biscuits were probably baked on stones in the Neolithic era. Archaeological remains of cooked grains do not show the form they took (cakes, porridges, or flat, crisp biscuits). But it’s a high likelihood that biscuits were on the menu.

The Romans had biscuits. We now call those old Roman foods “rusk.” Which was essentially bread that was re-baked to make it crisp. Twice cooking the bread meant it kept longer than plain bread. This made “panis biscotus” very useful as rations for travelers and soldiers.

So the next time you butter your biscuit, take a minute to think of all those ancient travelers who ate biscuits before you.

Pies, Cobblers, Crisps, and Ice Cream

Traditional Desserts For Your 4th of July Feast!

Are Pies One Of The Worlds Oldest Foods?

Did you know pie has been around since the ancient Egyptians? Then the Romans, who may have learned about pie from the Greeks, spread the word about pies around Europe. The Romans published the first pie recipe, rye-crusted goat cheese, and honey pie.

Pyes (British spelling) originally appeared in England as early as the twelfth century. The pie crust was referred to as “coffyn” (that would be coffin for those using U.S. spelling) and often not eaten. The “coffin” was just there to hold the filling.

Early pies were usually meat pies, and sometimes these pies were made using fowl with the legs left to hang over the side to be used as handles. Remember the old nursery rhyme “Sing a Song of Sixpence” with “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie?”

Fruit pies probably came along in the 1500s. English tradition credits the first cherry pie to Queen Elizabeth I. From England, pie jumped the pond with the first English settlers. But it wasn’t until the American Revolution that the term crust was used instead of coffin.

As the years went by, pie evolved to become what today is a traditional American dessert. Pie is so much a part of American culture we commonly use the phrase “as American as apple pie!”

Cobblers, More Traditionally American than Pie?

Cobblers originated in the American colonies. English settlers couldn’t make traditional suet puddings as they lacked many ingredients and cooking equipment. Using ingenuity and what they had on hand, they covered their fillings with a layer of uncooked plain biscuits (remember Biscuits up above?), scones, or dumplings.

Early colonists were so fond of these sweet juicy dishes that they often served them as breakfast or as a first course. It was only in the late 19th century that cobblers became desserts.

Cobblers are called by various names such as tart, torte, pandowdy, grunt, slump, buckles, and crisps. All of these variations are based on seasonal fruits and berries. In other words, using the fresh ingredients that you find throughout the year.

I prefer making a cobbler or a crisp to a pie, mostly because I’ve never really mastered the way to make a flaky tender pie crust. My favorite is the Peach Cobbler I learned from my Grandmother. Homemade cobblers are simple to make and rely more on taste than complicated pastry preparation.

“I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream For Ice Cream!” – Howard Johnson c 1927

According to the International Dairy Foods Association

“Ice cream’s origins are known to reach back as far as the second century BCE. However, no specific date of origin nor inventor has been undisputably credited with its discovery.”

There is a record of the first creamy texture introduced to flavored ice around 400 BCE in the Persian Empire. Vermicelli was combined with frozen rose water, saffron, and fruits to make for a luxurious dessert enjoyed by the royal family.

The Persians were off to a good start, but the brilliant minds behind ice cream are found further east and many centuries later. In China, around 200 CE, ice cream with a creamy dairy texture came to life as a mixture of frozen milk and rice pudding.

So, how did ice cream get to the Western world? Marco Polo. When Polo traveled to China in the last 12th century, he picked up on the Chinese production method. He introduced it back in Italy upon his return.

Catherine de Medici introduced France to these frozen desserts in 1553 when she became the wife of Henry II of France. A Sicilian named Procopio introduced a recipe blending milk, cream, butter, and eggs at Café Procope around 1660, finally making ice cream available to the general public. Incidentally, England appears to have discovered ice cream around the same time as “Cream Ice” was regularly featured on the table of Charles I during the 17th century.

Well known and loved in the “Old World,” it only makes sense that the immigrants to the “New World” brought the recipes and methods of making ice cream with them. We see an advertisement for ice cream in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1977. And records kept by a New York merchant show President George Washington spent approximately $200 on ice cream in 1790.

Today the U.S. is the largest producer and consumer of ice cream in the world. And don’t most of us prefer our pie “al a mode?”

Want to try your hand at making ice cream at home? It’s easier than ever with one of these automatic ice makers. Fresh ice cream is only a couple of short hours away.

How Many Countries Are Represented On Your Table?

When you sit down with friends and family this 4th of July, take a look around at the people and the food. Your table, like mine, most likely represents the cultural “salad bowl” that is the USA, with people, foods, and flavors from Scotland to Japan and Italy to the original Indigenous Americans.